Discussions

One day, I ran into SwissTable—the kind of design that makes you squint, grin, and immediately regret every naive linear-probing table you’ve ever shipped.

This post is the story of how I tried to bring that same “why is this so fast?” feeling into Java. It’s part deep dive, part engineering diary, and part cautionary tale about performance work.

1) The SwissTable project, explained the way it feels when you first understand it

SwissTable is an open-addressing hash table design that came out of Google’s work and was famously presented as a new C++ hash table approach (and later shipped in Abseil).

At a high level, it still does the usual hash-table thing: compute hash(key), pick a starting slot, and probe until you find your key or an empty slot.

The twist is that SwissTable separates metadata (tiny “control bytes”) from the actual key/value storage, and it uses those control bytes to avoid expensive key comparisons most of the time. Instead of immediately touching a bunch of keys (which are cold in cache and often pointer-heavy), it first scans a compact control bytes that is dense, cache-friendly, and easy to compare in bulk. If this feels like a tiny Bloom filter, you’re on the right track: the control bytes act as a cheap “maybe” gate before we pay for real key comparisons.

To make probing cheap, SwissTable effectively splits the hash into two parts: h1 and h2. Think of h1 as the part that chooses where to start probing (which group to look at first), and h2 as a tiny fingerprint stored in the control bytes to quickly rule slots in or out. It’s not a full hash—just enough bits to filter candidates before we pay the cost of touching real keys.

So on lookup, you compute a hash, derive (h1, h2), jump to the group from h1, and compare h2 against all control bytes in that group before you even look at any keys. That means most misses (and many hits) avoid touching key memory entirely until the metadata says “there’s a plausible candidate here.”

Because probing stays cheap, SwissTable can tolerate higher load factors—up to about 87.5% (7/8) in implementations like Abseil’s flat_hash_map—without falling off a performance cliff, which directly improves memory efficiency.

The net effect is a design that is simultaneously faster (fewer cache misses, fewer key compares) and tighter (higher load factor, fewer side structures like overflow buckets).

2) Watching SwissTable become the “default vibe” in multiple languages (Go, Rust)

The first sign you’re looking at a generational design is when it stops being a cool library trick and starts showing up in standard libraries.

Starting in Rust 1.36.0, std::collections::HashMap switched to the SwissTable-based hashbrown implementation. It’s described as using quadratic probing and SIMD lookup, which is basically SwissTable territory in spirit and technique. That was my “okay, this isn’t niche” moment.

Then Go joined the party: Go 1.24 ships a new built-in map implementation based on the Swiss Table design, straight from the Go team’s own blog post. In their microbenchmarks, map operations are reported to be up to 60% faster than Go 1.23, and in full application benchmarks they saw about a 1.5% geometric-mean CPU time improvement. And if you want a very practical “this matters in real systems” story, Datadog wrote about Go 1.24’s SwissTable-based maps and how the new layout and growth strategy can translate into serious memory improvements at scale.

At that point, SwissTable stopped feeling like “a clever C++ trick” and started feeling like the modern baseline. I couldn’t shake the thought: Rust did it, Go shipped it… so why not Java? And with modern CPUs, a strong JIT, and the Vector API finally within reach, it felt less like a technical impossibility and more like an itch I had to scratch.

That’s how I fell into the rabbit hole.

3) SwissTable’s secret sauce meets the Java Vector API

A big part of SwissTable’s speed comes from doing comparisons wide: checking many control bytes in one go instead of looping byte-by-byte and branching constantly. That’s exactly the kind of workload SIMD is great at: load a small block, compare against a broadcasted value, get a bitmask of matches, and only then branch into “slow path” key comparisons. In other words, SwissTable is not just “open addressing done well”—it’s “open addressing shaped to fit modern CPUs.”

Historically, doing this portably in Java was awkward: you either trusted auto-vectorization, used Unsafe, wrote JNI, or accepted the scalar loop. But the Vector API has been incubating specifically to let Java express vector computations that reliably compile down to good SIMD instructions on supported CPUs.

In Java 25, the Vector API is still incubating and lives in jdk.incubator.vector. The important part for me wasn’t “is it final?"—it was “is it usable enough to express the SwissTable control-byte scan cleanly?” Because if I can write “compare 16 bytes, produce a mask, act on set bits” in plain Java, the rest of SwissTable becomes mostly careful data layout and resizing logic. And once you see the control-byte scan as the hot path, you start designing everything else to make that scan cheap and predictable.

So yes: the Vector API was the permission slip I needed to try something I’d normally dismiss as “too low-level for Java.”

4) So I started implementing it (and immediately learned what Java makes easy vs. hard)

I began with the core SwissTable separation: a compact control array plus separate key/value storage. The control bytes are the main character—if those stay hot in cache and the scan stays branch-light, the table feels fast even before micro-optimizations.

I used the familiar h1/h2 split idea: h1 selects the initial group, while h2 is the small fingerprint stored in the control byte to filter candidates. Lookup became a two-stage pipeline: (1) vector-scan the control bytes for h2 matches, (2) for each match, compare the actual key to confirm. Insertion reused the same scan, but with an extra “find first empty slot” path once we know the key doesn’t already exist.

Where Java started pushing back was layout realism.

In C++ you can pack keys/values tightly; in Java, object references mean the “key array” is still an array of pointers, and touching keys can still be a cache-miss parade. So the design goal became: touch keys as late as possible, and when you must touch them, touch as few as possible—again, the SwissTable worldview.

Deletion required tombstones (a “deleted but not empty” marker) so probing doesn’t break, but tombstones also accumulate and can quietly degrade performance if you never clean them up.

Resizing was its own mini-project: doing a full rehash is expensive, but clever growth strategies (like Go’s use of table splitting/extendible hashing) show how far you can take this if you’re willing to complicate the design.

I also had to treat the Vector API as an optimization tool, not a magic wand. Vector code is sensitive to how you load bytes, how you handle tails, and whether the JIT can keep the loop structure stable. I ended up writing the control-byte scan as a very explicit “load → compare → mask → iterate matches” loop.

At this stage, the prototype already worked, but it wasn’t yet “SwissTable fast”—it was “promising, and now the real work begins.”

5) The pieces of SwissMap that actually mattered

Here’s what survived the usual round of “this feels clever but isn’t fast” refactors.

Control bytes & layout

With non-primitive keys, the real cost is rarely “a few extra byte reads” — it’s pointer chasing. Even one equals() can walk cold objects and pay cache-miss latency. So SwissMap treats the ctrl array as the first line of defense: scan a tight, cache-friendly byte array to narrow the search to a handful of plausible slots before touching any keys/values.

This matters even more in Java because “keys/values” usually means arrays of references. On 64-bit JVMs, compressed oops (often enabled up to ~32GB depending on alignment/JVM flags) packs references into 32 bits, making the reference arrays denser. When compressed oops is off, references widen to 64 bits and the same number of key touches can spill across more cache lines.

Either way, the ctrl array does most of the work: most misses die in metadata. Compressed oops just makes the unavoidable key touches cheaper when they do happen.

Load factor

In classic open addressing, pushing load factor up usually means the average probe chain gets longer fast — more branches, more random memory touches, and a steep cliff in miss cost. That’s why many general-purpose hash maps pick conservative defaults. Java’s HashMap, for example, defaults to a 0.75 load factor to keep miss costs from ballooning as the table fills.

SwissTable flips the cost model: probing is dominated by scanning the ctrl bytes first, which are dense, cache-friendly, and cheap to compare in bulk. That means “one more probe group” is often just one more ctrl-vector load + compare, not a bunch of key equals() calls. With SwissTable-style probing, the table can run denser without falling off a cliff. Abseil’s SwissTable-family maps are well known for targeting a ~7/8 (0.875) maximum load factor; even when the table is crowded, most probes are still “just metadata work.”

That trade-off is exactly what I wanted in Java too: higher load factor → fewer slots → smaller key/value arrays → fewer cache lines touched per operation, as long as the ctrl scan stays the fast path.

Sentinel padding

SIMD wants fixed-width loads: 16 or 32 control bytes at a time. The annoying part is the tail — the last group near the end of the ctrl array. In native code you might “over-read” a few bytes and rely on adjacent memory being harmless. In Java you don’t get that luxury: out-of-bounds is a hard stop.

Without padding, the probe loop picks up tail handling: extra bounds checks, masked loads, or end-of-array branches — exactly the kind of bookkeeping you don’t want in the hottest path. A small sentinel padding region at the end of the array lets every probe issue the same vector load, keeping the loop predictable and JIT-friendly.

H1/H2 split

Split the hash into h1 (which selects the starting group) and h2 (a small fingerprint stored per slot in the ctrl byte). h1 drives the probe sequence (usually via a power-of-two mask), while h2 is a cheap first-stage filter: SIMD-compare h2 against an entire group of control bytes and only touch keys for the matching lanes.

SwissMap uses 7 bits for h2, leaving the remaining ctrl-byte values for special states like EMPTY and DELETED. That’s the neat trick: one byte answers both:

- “Is this slot full/empty/deleted?”

- “Is this slot even worth a key compare?”

Most lookups reject non-matches in the control plane. And if a probed group contains an EMPTY, that’s a definitive stop signal: the probe chain was never continued past that point, so the key can’t exist “later.”

Reusing the loaded control vector

A ByteVector load isn’t free — it’s a real SIMD-width memory load of control bytes. On my test box, that load alone was ~6ns per probed group. In a hash table where a get() might be only a few dozen nanoseconds, that’s a meaningful tax.

So SwissMap tries hard to load the ctrl vector exactly once per group and reuse it:

- use the same loaded vector for the

h2equality mask (candidate lanes) - and again for the

EMPTY/DELETEDmasks (stop/continue decisions)

No extra passes, no “just load it again,” no duplicate work.

Tombstones

Deletion in open addressing is where correctness bites: if you mark a removed slot as EMPTY, you can break the probe chain. Keys inserted later in that chain would become “invisible” because lookups stop at the first empty.

Tombstones solve that by marking the slot as DELETED (“deleted but not empty”), so lookups keep probing past it.

Reusing tombstones on put

On put, tombstones are not just a correctness hack — they’re also reusable space. The common pattern is:

- during probing, remember the first

DELETEDslot you see - keep probing until you either find the key (update) or hit an

EMPTY(definitive miss) - if the key wasn’t found, insert into the remembered tombstone rather than the later empty slot

That tends to keep probe chains from getting longer over time, reduces resize pressure, and prevents workloads with lots of remove/put cycles from slowly poisoning performance.

When tombstones force a same-capacity rehash

Tombstones preserve correctness, but they dilute the strongest early-exit signal: EMPTY. A table with lots of DELETED tends to probe farther on misses and inserts — more ctrl scans, more vector loads, and more chances to touch cold keys.

So SwissMap tracks tombstones and triggers a same-capacity rehash when they cross a threshold (as a fraction of capacity or relative to live entries). This rebuilds the ctrl array, turning DELETED back into EMPTY and restoring short probe chains — basically compaction without changing logical contents.

A resize rehash without redundant checks

Resizing forces a rehash because h1 depends on capacity. The obvious approach is “iterate old entries and call put into the new table,” but that pays for work you don’t need: duplicate checks, extra branching, and unnecessary key equality calls.

The faster path treats resize as a pure move:

- allocate fresh ctrl/key/value arrays

- reset counters

- scan the old table once, and for each

FULLslot:- recompute

(h1, h2)for the new capacity - insert into the first available slot found by the same ctrl-byte probe loop

- without checking “does this key already exist?” (it can’t: you’re moving unique keys)

- recompute

This makes resizing a predictable linear pass over memory rather than a branchy series of full put() operations.

Iterators without extra buffers

Iteration is another place where “simple” becomes surprisingly expensive. You can scan linearly and yield FULL slots, but many designs want a stable-ish visit pattern without allocating a separate dense list. And some reinsertion/rehash interactions can even go accidentally quadratic (see the Rust iteration write-up).

SwissMap avoids extra buffers by iterating with a modular stepping permutation:

pick a start and an odd step (with power-of-two capacity, any odd step is coprime), then visit indices via repeated idx = (idx + step) & mask. This hits every slot exactly once, spreads accesses across the table, and keeps iteration as a tight loop over the same ctrl-byte state machine used elsewhere.

Here’s a trimmed version of the lookup to show how the probe loop hangs together around the control bytes:

protected int findIndex(Object key) {

if (size == 0) return -1;

int h = hash(key);

int h1 = h1(h);

byte h2 = h2(h);

int nGroups = numGroups();

int visitedGroups = 0;

int mask = nGroups - 1;

int g = h1 & mask; // optimized modulo operation (same as h1 % nGroups)

for (;;) {

int base = g * DEFAULT_GROUP_SIZE;

ByteVector v = loadCtrlVector(base);

long eqMask = v.eq(h2).toLong();

while (eqMask != 0) {

int bit = Long.numberOfTrailingZeros(eqMask);

int idx = base + bit;

if (Objects.equals(keys[idx], key)) { // found

return idx;

}

eqMask &= eqMask - 1; // clear LSB

}

long emptyMask = v.eq(EMPTY).toLong(); // reuse loaded vector

if (emptyMask != 0) { // any empty in a probed group is a definitive miss in SwissTable-style probing

return -1;

}

if (++visitedGroups >= nGroups) { // guard against infinite probe when table is full of tombstones

return -1;

}

g = (g + 1) & mask;

}

}

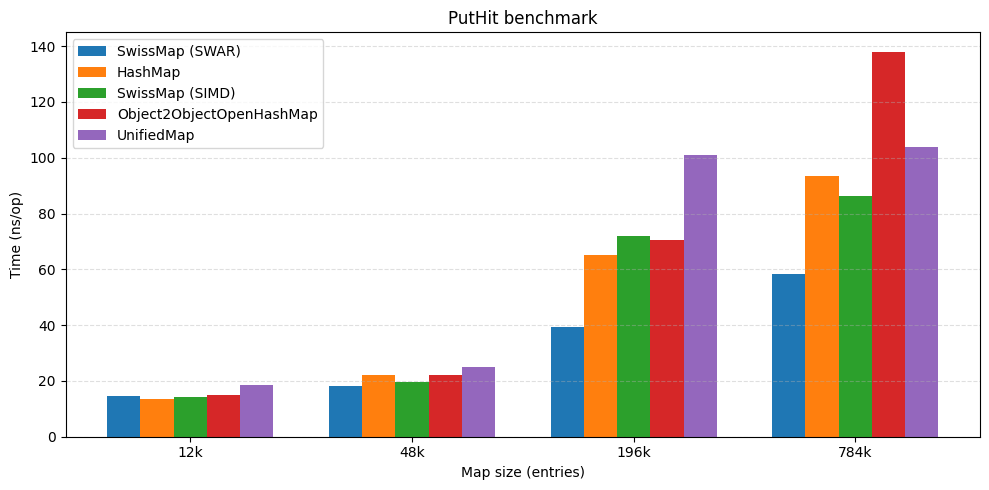

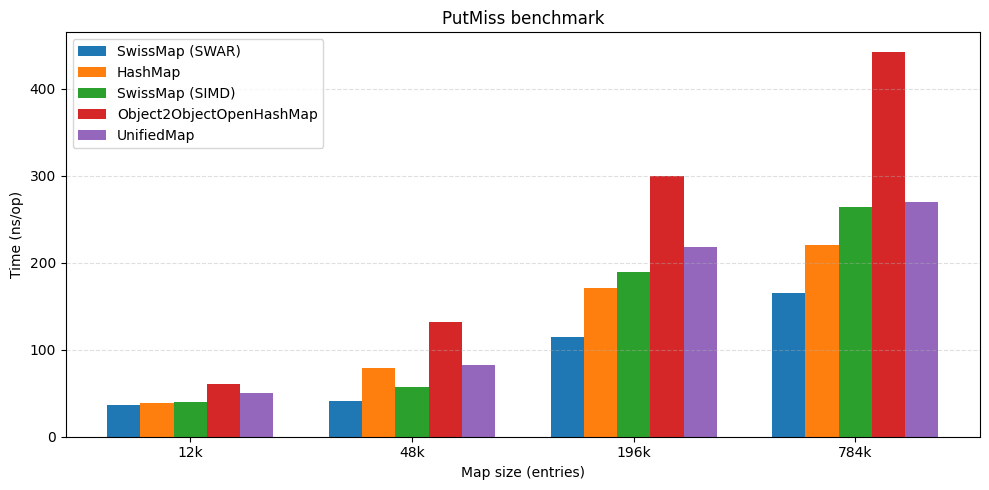

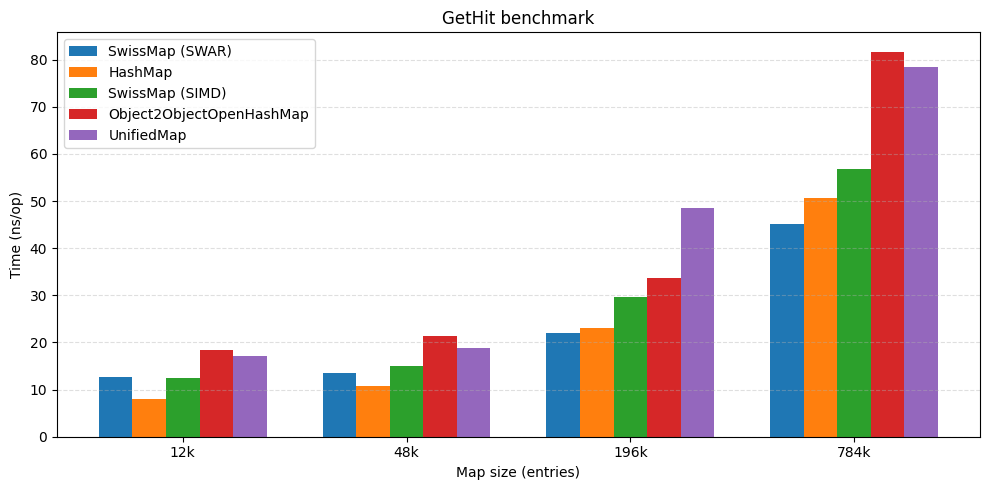

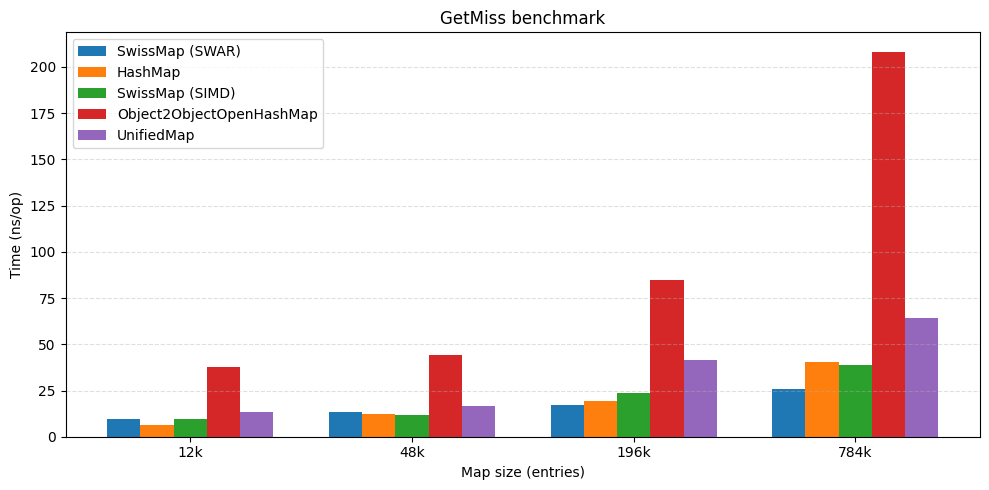

6) Benchmarks

I didn’t want to cherry-pick numbers that only look good on synthetic cases.

So I used a simple, repeatable JMH setup that stresses high-load probing and pointer-heavy keys—the exact situation SwissTable-style designs are meant to handle.

All benchmarks were run on Windows 11 (x64) with Eclipse Temurin JDK 21.0.9, on an AMD Ryzen 5 5600 (6C/12T).

For context, I compared against HashMap, fastutil’s Object2ObjectOpenHashMap, and Eclipse Collections’ UnifiedMap.

The headline result

At high load factors SwissMap keeps competitive throughput against other open-addressing tables and stays close to JDK HashMap performance. In some benchmarks it also comes out ahead by a large margin.

| put hit | put miss |

|---|---|

|  |

| get hit | get miss |

|---|---|

|  |

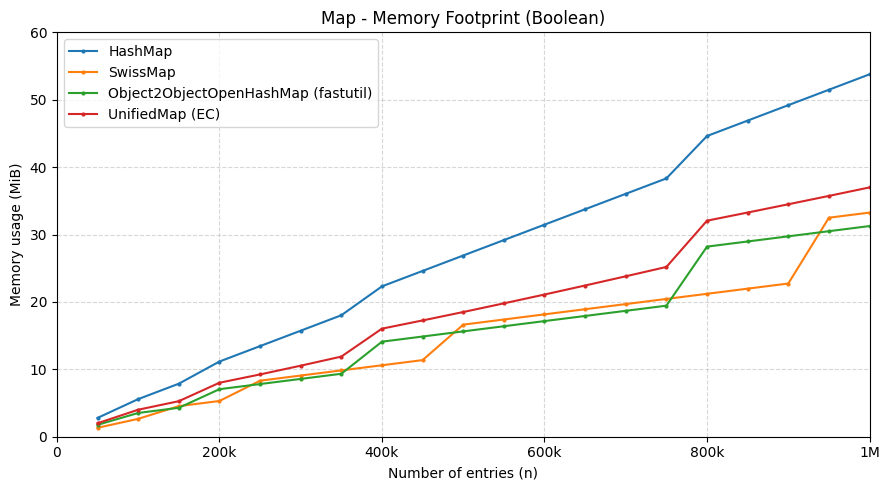

On memory, the flat layout (no buckets/overflow nodes) plus a 0.875 (7/8) max load factor translated to a noticeably smaller retained heap in small-payload scenarios—over 50% less than HashMap in this project’s measurements.

Caveat

These numbers are pre-release; the Vector API is still incubating, and the table is tuned for high-load, reference-key workloads. Expect different results with primitive-specialized maps or low-load-factor configurations.

Quick heads-up

You might notice a SWAR-style SwissTable variant appearing out of nowhere in the benchmark section. That version is part of a follow-up round of tuning: same SwissTable control-byte workflow, but implemented with SWAR to reduce overhead and avoid leaning on the incubating Vector API.

If SWAR is new to you, think of it as “SIMD within a register”: instead of using vector lanes, we pack multiple control bytes into a single 64-bit word and do the same kind of byte-wise comparisons with plain scalar instructions. The end result is a similar fast-path idea, just expressed in a more portable (and JDK-version-friendly) way.

I didn’t want this post to turn into three posts, so I’m saving the full “how/why” (SWAR included) for the next write-up — stay tuned.

P.S. If you want the code

This post is basically the narrative version of an experiment I’m building in public: HashSmith, a small collection of fast, memory-efficient hash tables for the JVM.

It includes SwissMap (SwissTable-inspired, SIMD-assisted probing via the incubating Vector API), plus a SwissSet variant to compare trade-offs side by side.

It’s explicitly experimental (not production-ready), but it comes with JMH benchmarks and docs so you can reproduce the numbers and poke at the implementation details.

If you want to run the benchmarks, sanity-check an edge case, or suggest a better probe/rehash strategy, I’d love issues/PRs

P.P.S. A great talk to watch

If you want the “straight from the source” version, Matt Kulukundis and other Google engineers’ CppCon talk on SwissTable is genuinely excellent — clear, practical, and packed with the kind of details that make the design click: CppCon talk.