Discussions

The next milestone is to build a fully thread-safe hash map.

Up to this point, the focus has been entirely on single-threaded performance: minimizing memory overhead, improving cache locality, and squeezing out every last bit of throughput from the underlying data layout. However, real-world applications rarely stay single-threaded. To be practically useful, a hash map must behave correctly—and efficiently—under concurrent access.

Before jumping straight into implementation, it’s worth stepping back and studying how existing thread-safe hash map implementations approach this problem. Different designs make different trade-offs between simplicity, scalability, memory usage, and read/write performance. By examining these approaches side by side, we can better understand which ideas scale cleanly—and where the pitfalls are—when multiple threads hit the same structure at once.

In this part, I’ll walk through the most common strategies used in real-world concurrent hash maps, and highlight the core trade-offs that shape their performance and complexity.

1) Global Lock (the synchronized approach)

The most straightforward way to make a hash map thread-safe is to wrap the entire implementation with a single global lock, effectively placing the same synchronization barrier around every public operation.

public V get(Object key) { synchronized (mutex) { ... } }

public V put(K key, V value) { synchronized (mutex) { ... } }

public V remove(Object key) { synchronized (mutex) { ... } }

With this approach, all methods are forced to acquire the exact same lock before accessing the internal state of the map.

This includes not only the obvious mutating operations such as put and remove, but also:

get,containsKeyresize,rehashclear,size- and essentially every other method that touches the internal data structures

From a correctness standpoint, this strategy is almost trivial to reason about. Thread safety is guaranteed entirely by the properties provided by the lock itself:

- Mutual exclusion ensures that only one thread can observe or mutate the map at any given time.

- Happens-before relationships established by entering and exiting the synchronized block ensure proper memory visibility between threads.

As a result, there is no need for additional volatile fields, memory fences, or fine-grained coordination logic. The implementation is simple, robust, and very hard to get wrong—which is precisely why this pattern is used by Collections.synchronizedMap and similar wrappers.

Of course, this simplicity comes at a cost. By serializing all operations behind a single lock, even read-only workloads suffer from contention, effectively reducing the map to single-threaded performance under concurrent access. This trade-off will become especially relevant once we compare this approach to more fine-grained concurrency strategies later on.

What a Java synchronized Block Really Does

At the bytecode level, the Java synchronized keyword is surprisingly simple.

Once compiled, a synchronized block is translated directly into a pair of bytecode instructions:

monitorenter: acquire the monitor associated with an objectmonitorexit: release that monitor

In other words, every synchronized block is built on top of an object monitor. A thread must successfully enter the monitor before executing the protected code, and it must exit the monitor when it leaves the block—whether normally or due to an exception.

However, in HotSpot, this monitor is not implemented as a single, heavyweight OS mutex in all cases. Doing so would make synchronized blocks far too expensive for common, low-contention scenarios.

Instead, HotSpot dynamically adapts its locking strategy based on how much contention it observes. Internally, object monitors transition through different states, most notably:

- Thin locks, which are optimized for uncontended or lightly contended cases

- Inflated locks, which are used once contention becomes significant

This adaptive behavior allows synchronized to be relatively cheap when only one thread (or a small number of threads) is involved, while still remaining correct under heavy contention. Of course, once a lock inflates, the cost becomes much closer to that of a traditional OS-level mutex—a detail that becomes important when evaluating global-lock-based designs for high-concurrency data structures.

Thin Lock: A Lightweight Fast Path

In HotSpot, every Java object starts with a small header. Conceptually, it contains two major pieces:

- mark word: a header word

- klass pointer: pointing to the object’s class metadata

Traditionally, HotSpot has used this mark word to encode several kinds of runtime metadata—things like the identity hash code, GC age/marking bits, and, crucially for us, locking state.

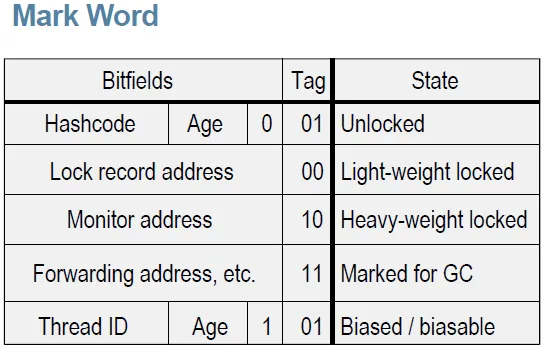

The diagram below, adapted from JP Bempel’s excellent write-up, shows the rough layout and how those bits get repurposed depending on the state. The exact lock states and header layout vary across HotSpot versions (for example, biased locking has been removed in recent JDKs); the diagram is provided for intuition, not as a current spec.

For reference, the current HotSpot source comments describe the mark word states roughly as follows:

// - the two lock bits are used to describe three states: locked/unlocked and monitor.

//

// [ptr | 00] locked // ptr points to real header on stack (stack-locking)

// [header | 00] locked // locked regular object header (fast-locking)

// [header | 01] unlocked // regular object header

// [ptr | 10] monitor // inflated lock (UseObjectMonitorTable == false)

// [header | 10] monitor // inflated lock (UseObjectMonitorTable == true)

// [ptr | 11] marked // used for GC marking

A thin lock (lightweight lock) uses that header space to avoid allocating a heavyweight monitor in the common case. The basic idea is simple: when a thread enters a synchronized block, the VM creates a lock record in the thread’s stack frame, and then tries to “install” a pointer to that lock record into the object’s header via an atomic compare-and-swap (CAS). If the CAS succeeds, the thread owns the lock.

This is why thin locking is usually cheap: in the uncontended case, it’s essentially a couple of predictable memory operations plus a single atomic instruction—no kernel involvement, no parked threads, and no heavyweight monitor bookkeeping.

But thin locks also have a natural limit. If two different threads truly contend on the same object at the same time, HotSpot may have to inflate the lock into a heavyweight monitor so it can manage a queue of waiting threads safely.

Inflated Lock: The Heavyweight Path

When contention becomes significant, a thin lock may no longer be able to make progress efficiently. In that case, HotSpot inflates the lock: instead of encoding ownership purely in the object header’s lightweight locking bits, the JVM associates the object with a dedicated runtime monitor structure.

Once a lock is inflated, ownership tracking and wait-queue management are handled by ObjectMonitor—HotSpot’s internal monitor implementation. The Java object then refers to that monitor either:

- directly via the object’s mark word (the traditional layout), or

- indirectly via an external mapping table (an

ObjectMonitorTable-style association), depending on the HotSpot implementation and configuration.

This matters because an inflated lock is no longer “just a couple of CAS operations on the header.” It becomes a full-fledged synchronization object that can manage contending threads, queueing, and blocking behavior.

At the implementation level, ObjectMonitor is a HotSpot runtime class implemented in native (C++) code inside the JVM.

If you skim through the source, you can see the high-level strategy pretty clearly: contending threads try to enqueue themselves using CAS, may spin briefly, and if the lock still doesn’t become available, they eventually fall back to parking (blocking) and later being unparked when the monitor becomes available.

bool ObjectMonitor::enter(JavaThread* current) {

assert(current == JavaThread::current(), "must be");

// try spin lock first

if (spin_enter(current)) {

return true;

}

...

// then try fallback to thread parking

enter_with_contention_mark(current, contention_mark);

return true;

}

void ObjectMonitor::enter_with_contention_mark(JavaThread* current, ObjectMonitorContentionMark &cm) {

...

enter_internal(current)

...

}

void ObjectMonitor::enter_internal(JavaThread* current) {

...

current->_ParkEvent->park();

...

}

Parking: when the JVM goes from spinning to actually blocking

At some point, spinning stops being a good deal. When contention is high (or the critical section is long), the JVM will eventually take the slow path: it will park the thread, letting the OS scheduler stop running it until it’s explicitly woken up again.

The exact mechanism depends on the operating system. On POSIX-like platforms (including Linux), HotSpot uses the POSIX backend in os_posix.cpp, where os::PlatformEvent::park() is responsible for blocking the current thread.

If you look at how os::PlatformEvent::park() is implemented on POSIX, you’ll notice that it is built around a classic mutex + condition variable pattern. In particular, it can call the POSIX primitive pthread_cond_wait(), which puts the thread into a waiting state until another thread signals it.

void PlatformEvent::park() {

...

while (_event < 0) {

status = pthread_cond_wait(_cond, _mutex);

assert_status(status == 0 MACOS_ONLY(|| status == ETIMEDOUT), status, "cond_wait");

}

...

}

Even after you land in pthread_cond_wait(), you’re not dealing with some opaque black box. On Linux, there’s a strong commonality: popular libcs implement pthread condition variables on top of the kernel’s futex (“fast userspace mutex”) mechanism—i.e., the familiar WAIT/WAKE pattern. Both glibc and musl follow this approach.

A futex is Linux’s kernel-backed primitive for “wait on (and wake from) a value in shared userspace memory”—the low-level building block that higher-level locks/condvars are built on. The man page describes futexes as follows:

The

futex()system call provides a method for waiting until a certain condition becomes true. It is typically used as a blocking construct in the context of shared-memory synchronization.

LWN has a great diagram showing how the Linux kernel organizes futex waiters once threads fall back to futex-based sleeping:

- Each futex operation is keyed by a userspace address (labeled key A). The kernel derives a

futex_keyfrom that address. - The key is fed into a hash function (

hash_futex()), which selects a bucket in the globalfutex_queueshash table (hb0 … hbN). Buckets are protected by lightweight locks. - Inside a bucket, the kernel maintains one or more

futex_qlists, each corresponding to a distinct futex key (i.e., a distinct userspace address). - When a thread calls

FUTEX_WAIT, it is enqueued into thefutex_qfor that key (e.g., Task A1 and A2 both wait on key A, so they end up in the same queue). - A

FUTEX_WAKEon a given address hashes to the same bucket, finds the matchingfutex_q, and dequeues one or more waiting tasks, making them runnable again.

The important point is that the kernel does not understand locks or condition variables here. It only manages wait queues indexed by memory addresses. All higher-level semantics (lock state, condition checks, ownership) live entirely in user space; the kernel just provides an efficient “sleep here / wake them up” service keyed by an address.

If you want to dig deeper into futexes, this write-up is a good place to start.

This is the key transition point: once we hit the futex slow path, the cost is no longer “just a few CAS retries.” We’re now paying for kernel-assisted blocking and waking, which implies context switches and scheduler involvement—exactly the kind of overhead that global-lock designs can trigger under heavy contention.

Pros & Cons

A single global lock has one obvious appeal: it’s incredibly simple. You don’t need to rethink the data structure or invent a new concurrency protocol—just wrap every operation in the same synchronized (or mutex) barrier and you immediately get mutual exclusion and the memory-visibility guarantees that come with it.

The downside is that this simplicity buys correctness by throwing away parallelism. Because every operation competes for the same lock, even read-only calls like get() end up blocking each other. In practice that means you get essentially zero read parallelism, so a workload that should scale nicely with more reader threads can collapse back into “one thread at a time.”

Worse, under real contention the cost isn’t just reduced throughput—it can become a latency problem. As contention increases, HotSpot tends to fall back to progressively heavier synchronization paths. What begins as a lightweight fast path can escalate into monitor inflation and eventually into parking, where threads actually block and rely on the OS scheduler to be woken up later. Once you’re in that regime, lock acquisition stops looking like “a few failed CAS attempts” and starts looking like “context switches and scheduler overhead,” which can make tail latency spike dramatically when many threads pile up behind a single global lock.

If you’d like a deeper dive into the trade-offs between spinning and blocking—especially what actually drives the overhead difference between spinlocks and mutex-style locks—this article is a solid reference: Spinlocks vs. Mutexes: When to Spin and When to Sleep

2) Lock Striping / Sharding (DashMap-style)

After the “one big lock” approach, the next most common step up is to split contention across multiple locks.

With lock striping, you pre-create a fixed number of locks—say N—and deterministically map each key to one of them. Conceptually it looks like:

- keep

Nlocks around, - compute

stripe = hash(key) % N(typically withNas a power of two), - and then only acquire the lock for that particular stripe while performing the operation.

The payoff is immediate: operations that fall into different stripes can run concurrently, which gives you real scalability compared to a single global lock. The trade-off is that the mapping is coarse-grained: two completely unrelated keys can still end up on the same stripe, and then they’ll block each other anyway—purely due to a stripe collision. Guava’s Striped utility is a widely used, reusable implementation of this pattern.

If striping is “multiple locks around one shared data structure,” sharding usually goes one step further: you split the data structure itself. Instead of one big map guarded by many locks, you keep multiple independent maps (or tables), each with its own lock, and route each key to exactly one shard based on its hash.

DashMap

Rust’s DashMap is a well-known example of this design. Internally it maintains an array of shards, and each shard combines “its own table + its own lock” (commonly described as a per-shard RwLock<HashMap<K, V>> in the mental model). The shard is chosen from the key’s hash, so operations targeting different shards generally don’t interfere with each other.

pub struct DashMap<K, V, S = RandomState> {

shift: usize,

shards: Box<[CachePadded<RwLock<HashMap<K, V>>>]>,

hasher: S,

}

A Quick Look at the Read Path

In DashMap, the get path is almost comically straightforward.

- Hash the key to a 64-bit value.

- Use that hash to pick a shard index.

- Grab the shard’s read lock, and then look up the entry inside that shard’s local table.

In code, it looks roughly like this:

fn _get<Q>(&'a self, key: &Q) -> Option<Ref<'a, K, V>>

where

Q: Hash + Equivalent<K> + ?Sized,

{

let hash = self.hash_u64(&key);

let idx = self.determine_shard(hash as usize);

let shard = self.shards[idx].read();

// SAFETY: The data will not outlive the guard, since we pass the guard to `Ref`.

let (guard, shard) = unsafe { RwLockReadGuardDetached::detach_from(shard) };

if let Some((k, v)) = shard.find(hash, |(k, _v)| key.equivalent(k)) {

Some(Ref::new(guard, k, v))

} else {

None

}

}

The only synchronization on the read path is the per-shard read() call. That’s the whole point of sharding: as long as two keys land in different shards, their readers don’t interfere with each other at all.

The Write Path: Same Shape, Different Lock

The write path looks almost identical to the read path. We still hash the key, compute the shard index, and then operate only on that shard. The only real difference is the kind of lock we acquire: instead of a read lock, we take the shard’s write lock, because we’re about to mutate the underlying table.

Here’s the core of DashMap’s entry-based write path:

fn _entry(&'a self, key: K) -> Entry<'a, K, V> {

let hash = self.hash_u64(&key);

let idx = self.determine_shard(hash as usize);

let shard = self.shards[idx].write();

// SAFETY: The data will not outlive the guard, since we pass the guard to `Entry`.

let (guard, shard) = unsafe { RwLockWriteGuardDetached::detach_from(shard) };

match shard.entry(

hash,

|(k, _v)| k == &key,

|(k, _v)| {

let mut hasher = self.hasher.build_hasher();

k.hash(&mut hasher);

hasher.finish()

},

) {

hash_table::Entry::Occupied(entry) => {

Entry::Occupied(OccupiedEntry::new(guard, key, entry))

}

hash_table::Entry::Vacant(entry) => Entry::Vacant(VacantEntry::new(guard, key, entry)),

}

}

Conceptually, this is the same story as the read path: hash → shard selection → lock → local table operation. The big difference is simply that taking the write lock makes this operation exclusive within that shard, which is exactly the behavior you want for mutations.

Why Use an RW Lock per Shard?

Within the sharded design, each shard uses an RW lock rather than a plain mutex. The motivation is simple: even inside the same shard, read–read access can proceed concurrently. That can be a big win for read-heavy workloads, where you’d otherwise serialize a huge fraction of operations for no real reason.

Of course, RW locks come with their own trade-offs. Depending on the implementation and scheduling policy, they can suffer from writer starvation (writers being delayed indefinitely under a steady stream of readers), and they also introduce extra overhead compared to a simple mutex—both in terms of lock bookkeeping and in the complexity of the fast path. So while RW locking improves parallelism for reads, it’s not automatically a net win; you still have to evaluate it in the context of the expected workload and contention patterns.

A Small Trick for Shard Selection in SwissTable-based Maps

DashMap uses hashbrown (SwissTable) internally, so it deliberately avoids consuming the top 7 hash bits when selecting a shard—those bits are reserved for SwissTable’s SIMD tag (H2). Instead, it derives the shard index from the remaining bits to prevent shard routing from biasing the per-shard tag distribution.

pub(crate) fn determine_shard(&self, hash: usize) -> usize {

// Leave the high 7 bits for the HashBrown SIMD tag.

let idx = (hash << 7) >> self.shift;

// hint to llvm that the panic bounds check can be removed

if idx >= self.shards.len() {

if cfg!(debug_assertions) {

unreachable!("invalid shard index")

} else {

// SAFETY: shards is always a power of two,

// and shift is calculated such that the resulting idx is always

// less than the shards length

unsafe {

std::hint::unreachable_unchecked();

}

}

}

idx

}

Choosing the Number of Shards

A common rule of thumb is to size the shard count as a power of two that is comfortably larger than the number of concurrent threads.

DashMap also picks a fairly aggressive default for the number of shards. It starts from the machine’s available parallelism, multiplies it by 4, and then rounds up to the next power of two. This keeps shard selection fast (a simple mask) while intentionally over-sharding a bit to reduce contention under multi-threaded workloads

fn default_shard_amount() -> usize {

static DEFAULT_SHARD_AMOUNT: OnceLock<usize> = OnceLock::new();

*DEFAULT_SHARD_AMOUNT.get_or_init(|| {

(std::thread::available_parallelism().map_or(1, usize::from) * 4).next_power_of_two()

})

}

Computing Capacity

DashMap keeps capacity as a shard-local property. Since each shard owns its own underlying table, there isn’t a single “global capacity” field that can be read cheaply and accurately. Instead, when you need the map’s overall capacity, DashMap computes it on demand by summing the capacity of each shard:

fn _capacity(&self) -> usize {

self.shards.iter().map(|s| s.read().capacity()).sum()

}

This matches the sharded growth model nicely. Resizing happens independently per shard, so the map doesn’t need to constantly maintain or recompute a global size/capacity value just to decide when to grow. In other words, the hot path can stay focused on the shard you’re touching, and the “global” view is only assembled when you explicitly ask for it.

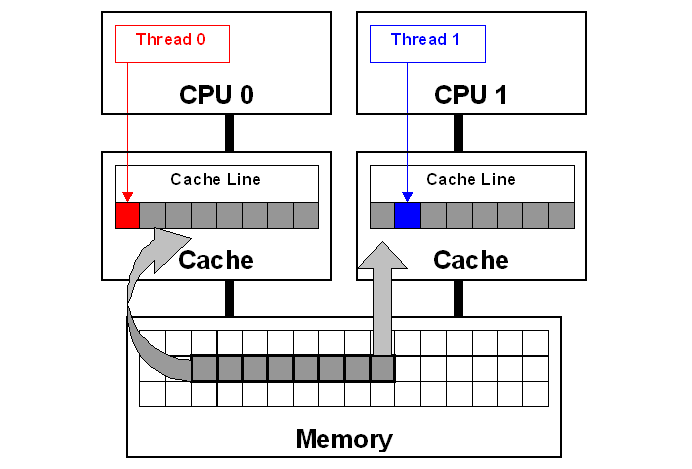

Why use CachePadded? (A Subtle but Crucial Optimization)

In Rust, Box<[T]> is an owned slice: conceptually, it represents a single heap allocation large enough to hold len * size_of::<T>() bytes (for non–zero-sized T), with the elements laid out contiguously as T, T, T, .... On the stack you keep a “fat pointer” (data pointer + length), but the backing storage itself is one contiguous block on the heap.

Now consider what a sharded design often looks like: a contiguous array of shards, where each shard is something like an RwLock<HashMap<K, V>>. Conceptually, an RwLock<T> stores the lock state (atomics/flags, bookkeeping for waiters, etc.) alongside the protected value T—in this case, a HashMap—as part of a single structure.

If those shards are then stored in something like a boxed slice, they end up adjacent in memory, sitting next to each other in a tightly packed layout.

That tight packing can backfire under contention. Lock state tends to be updated very frequently and those updates can cause false sharing: independent shards that happen to live on the same cache line can end up invalidating each other’s cache lines, creating unnecessary cache-line bouncing across cores.

CachePadded<T> is a pragmatic fix for this. It wraps a value and adds enough padding and alignment so that it is much more likely to occupy its own cache line, reducing false sharing between neighboring lock states. This doesn’t change the algorithm, but it can significantly improve real-world throughput when many threads hammer different shards concurrently.

What’s a Cache Line, Anyway?

A cache line is the basic unit the CPU cache uses to move data around and to maintain coherence between cores. When people talk about “cache-friendly” layouts or “cache-line bouncing,” this is the granularity they’re referring to.

On most modern mainstream CPUs, a cache line is typically 64 bytes.

The key detail is that CPUs don’t fetch memory one byte at a time. When a core reads from memory, it usually pulls in the entire cache line containing that address. So even if your code only touches an 8-byte value, the CPU may load the surrounding bytes as well—up to a full 64B line—because that’s the unit of transfer.

This design is a direct bet on spatial locality: if you accessed one address, chances are you’ll soon access nearby addresses too, so pulling in adjacent bytes often pays off.

But the same mechanism is also what makes false sharing possible.

What is False Sharing?

To understand false sharing, it helps to remember how caches work at the hardware level: when a CPU reads from memory, it doesn’t pull in a single byte or a single integer—it pulls in a fixed-size cache line.

That “fixed-size chunk” detail has an unintuitive consequence. Two small, completely unrelated pieces of data—say two int32s—can end up sitting next to each other in memory, and therefore inside the same cache line.

Now imagine two different CPU cores, each running a different thread, and each thread repeatedly updates one of those variables:

// Assume x and y are in the same cache line

int x = 0;

int y = 0;

// Thread 1

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

x++;

}

// Thread 2

for (int i = 0; i < 1000; ++i) {

y++;

}

From the programmer’s perspective, these threads are not sharing anything. Thread 1 touches x, thread 2 touches y, end of story.

But the cache coherence protocol doesn’t track ownership at the level of individual variables—it tracks it at the level of cache lines. When one core modifies any byte within a cache line, that line has to transition into a writable state for that core, and other cores’ cached copies of the same line may be invalidated. So even though the threads never touch the same variable, they keep fighting over ownership of the same cache line. The line bounces back and forth between cores, and performance collapses.

That is false sharing: independent variables “accidentally” share a cache line, and the hardware ends up treating them like shared data because coherence is managed at cache-line granularity.

Below is a practical illustration from the Netflix Tech Blog showing how false sharing happens at cache-line granularity.

False sharing shows up as a very real microarchitectural tax. Once two cores start bouncing the same cache line back and forth, every write forces coherence traffic and invalidations, and the affected cores spend more time waiting for the line to arrive in the right coherence state. That waiting manifests as pipeline stalls, which in turn drives CPI (cycles per instruction) up—your loop is still “doing the same amount of work,” but it’s retiring far fewer useful instructions per cycle.

At the same time, the cache hierarchy gets hammered. Because the line keeps getting invalidated and re-fetched, you end up repeatedly evicting and reloading the same 64-byte line. Even though the data set is tiny, the system is effectively forced into a high-frequency “empty and refill” pattern, pushing up the effective bandwidth pressure on the caches and the coherence interconnect. In practice, this can look like inflated L1/L2/L3 traffic and reduced headroom for everything else running on the machine.

If you want to go deeper on how false sharing shows up in real systems, Netflix has a fantastic write-up that’s well worth reading.

3) The Java 8+ ConcurrentHashMap Approach

Java’s ConcurrentHashMap (CHM) takes a very different approach from both global locking and classic sharding. Its core philosophy can be summarized as:

“Do as much work as possible with CAS, fall back to locking only when absolutely necessary—and even then, lock only a tiny portion of the structure. When resizing is required, let multiple threads cooperate to get it done.”

At the heart of the data structure is a single, volatile array:

transient volatile Node<K, V>[] table;

This array serves as the primary storage. Each element in the array is called a bin, and each bin holds the entries whose hashes map to that index.

In the common case, a bin is implemented as a simple linked list of Node<K, V> instances. However, when collisions become severe and a bin grows beyond a certain threshold, CHM dynamically converts that bin into a red–black tree (represented internally by TreeBin and TreeNode). This adaptive behavior keeps lookup time bounded even under adversarial or highly skewed hash distributions.

The table size itself is always maintained as a power of two, chosen as the smallest power-of-two capacity that can hold the requested number of entries. This allows index computation to be reduced to a fast bitmask operation rather than an expensive modulo.

private static final int tableSizeFor(int c) {

int n = -1 >>> Integer.numberOfLeadingZeros(c - 1);

return (n < 0) ? 1 : (n >= MAXIMUM_CAPACITY) ? MAXIMUM_CAPACITY : n + 1;

}

Viewed from a high level, CHM is effectively applying sharding at the data level. Each bin acts as a tiny, independent contention domain: updates to different bins can proceed concurrently, and even when locking is required, the lock is scoped to a single bin rather than the entire table. This fine-grained design is what allows ConcurrentHashMap to scale well under high concurrency without relying on coarse global locks.

How ConcurrentHashMap.put() Works

ConcurrentHashMap.put() is built around a simple idea: try to finish the operation with a cheap, CAS step first, and only if that fails, fall back to locking—and even then, lock as little as possible.

It starts by hashing the key and computing the target bin index using a power-of-two mask ((n - 1) & hash). If the corresponding slot in the table is empty, put() takes the fastest route: it attempts to install the first Node into that bin with a single CAS. When this succeeds, the insertion completes without taking any locks at all.

If the bin isn’t empty, the next question is whether it’s even safe to insert there. When the first node indicates a MOVED state, the map is in the middle of a resize, so put() doesn’t blindly mutate the old table. Instead it follows the forwarding logic—typically helping with the transfer or retrying the operation against the new table.

In the normal case (not MOVED), put() does a quick check on the bin’s head node as a small fast path. But if it can’t resolve the update immediately, it falls back to the contended path: it synchronizes on the bin’s first node and performs the insertion while holding that monitor. This is the key design point—locking is scoped to a single bin, not the entire map.

Inside that tiny critical section, the actual insertion depends on how the bin is represented. If it’s still a linked list, it walks the nodes in order, updating the value if the key already exists or appending a new node otherwise. If the bin has been treeified, the head points to a TreeBin wrapper and the operation becomes a red–black tree lookup/insert over TreeNode instead. Either way, the important part is that contention is localized: threads inserting into different bins can proceed independently, and even heavy contention only serializes threads that collide on the same bin.

final V putVal(K key, V value, boolean onlyIfAbsent) {

if (key == null || value == null) throw new NullPointerException();

int hash = spread(key.hashCode());

int binCount = 0;

for (Node<K,V>[] tab = table;;) {

Node<K,V> f; int n, i, fh; K fk; V fv;

if (tab == null || (n = tab.length) == 0)

tab = initTable();

else if ((f = tabAt(tab, i = (n - 1) & hash)) == null) {

if (casTabAt(tab, i, null, new Node<K,V>(hash, key, value)))

break; // no lock when adding to empty bin

}

else if ((fh = f.hash) == MOVED)

tab = helpTransfer(tab, f);

else if (onlyIfAbsent // check first node without acquiring lock

&& fh == hash

&& ((fk = f.key) == key || (fk != null && key.equals(fk)))

&& (fv = f.val) != null)

return fv;

else {

V oldVal = null;

synchronized (f) { // <<<< core insert logic here

if (tabAt(tab, i) == f) {

if (fh >= 0) {

binCount = 1;

for (Node<K,V> e = f;; ++binCount) {

K ek;

if (e.hash == hash &&

((ek = e.key) == key ||

(ek != null && key.equals(ek)))) {

oldVal = e.val;

if (!onlyIfAbsent)

e.val = value;

break;

}

Node<K,V> pred = e;

if ((e = e.next) == null) {

pred.next = new Node<K,V>(hash, key, value);

break;

}

}

}

else if (f instanceof TreeBin) {

Node<K,V> p;

binCount = 2;

if ((p = ((TreeBin<K,V>)f).putTreeVal(hash, key,

value)) != null) {

oldVal = p.val;

if (!onlyIfAbsent)

p.val = value;

}

}

else if (f instanceof ReservationNode)

throw new IllegalStateException("Recursive update");

}

}

if (binCount != 0) {

if (binCount >= TREEIFY_THRESHOLD)

treeifyBin(tab, i);

if (oldVal != null)

return oldVal;

break;

}

}

}

addCount(1L, binCount);

return null;

}

Treeification: when a bin stops being a linked list

When a particular bin accumulates too many colliding entries—i.e., the bin’s node count exceeds TREEIFY_THRESHOLD —ConcurrentHashMap may convert that bin from a simple linked list into a red–black tree. The goal is straightforward: once collision chains get long, linear scans become expensive, so CHM switches to a structure with bounded lookup/insertion cost.

That said, treeification is not unconditional. If the overall table is still “too small,” CHM will usually resize the table instead of treeifying the bin. The reasoning is that a small table is more likely to produce collisions simply because there aren’t enough bins; growing the table often fixes the problem more effectively than paying the constant-factor cost of maintaining a tree.

/**

* Replaces all linked nodes in bin at given index unless table is

* too small, in which case resizes instead.

*/

private final void treeifyBin(Node<K,V>[] tab, int index) {

Node<K,V> b; int n;

if (tab != null) {

if ((n = tab.length) < MIN_TREEIFY_CAPACITY)

tryPresize(n << 1);

else if ((b = tabAt(tab, index)) != null && b.hash >= 0) {

synchronized (b) {

if (tabAt(tab, index) == b) {

TreeNode<K,V> hd = null, tl = null;

for (Node<K,V> e = b; e != null; e = e.next) {

TreeNode<K,V> p =

new TreeNode<K,V>(e.hash, e.key, e.val,

null, null);

if ((p.prev = tl) == null)

hd = p;

else

tl.next = p;

tl = p;

}

setTabAt(tab, index, new TreeBin<K,V>(hd));

}

}

}

}

}

A couple of subtle design choices are worth noticing here.

First, CHM synchronizes only on the bin head (synchronized (b)), keeping the locking scope as small as possible.

Second, it re-checks that the bin head hasn’t changed (tabAt(tab, index) == b) after acquiring the lock—this is a common pattern in CHM to avoid races where another thread reshapes the bin concurrently. This extra check after acquiring the lock is reminiscent of double-checked locking

Finally, the conversion itself is mechanical: it walks the existing linked list and rebuilds it as a chain of TreeNodes, then installs a TreeBin wrapper into table[index] to represent the new tree-based bin.

Why ConcurrentHashMap Can Afford a Simple Hash Spread

Treeification gives ConcurrentHashMap a useful “safety net” against pathological collisions. Once a bin gets too large, CHM can convert it from a linked list into a balanced tree, which bounds the lookup/insert cost for that bin to O(log n) rather than degrading all the way to linear scans. In other words, even under high-collision scenarios, the data structure becomes much less sensitive to long collision chains because the probe length stops growing linearly with the number of colliding keys.

This property also influences how much effort CHM needs to spend on “perfectly spreading” hashes. Since the implementation has a backstop that prevents bins from becoming arbitrarily slow, it can afford to keep the hash-spreading step relatively lightweight—typically just a small bit-mixing function before applying the power-of-two mask.

static final int spread(int h) {

return (h ^ (h >>> 16)) & HASH_BITS;

}

And that matters because in low-level data structures like hash maps, the cost of hashing is often a meaningful part of the total CPU budget. In many workloads, you’re not just paying for a couple of pointer-chases—you’re also paying to compute hashes (sometimes repeatedly), and that work can dominate or at least noticeably affect end-to-end performance.

Poisson Bin Sizes in the “Normal” Case

One of the more interesting details is that ConcurrentHashMap’s own source comments explicitly argue that, in realistic workloads with well-distributed hashes, long bins are statistically rare. Under random hash codes, and assuming a resize threshold (load factor) of 0.75, the distribution of bin sizes is said to be well-approximated by a Poisson distribution with λ ≈ 0.5 (with the caveat that resizing granularity introduces large variance).

If you ignore that variance and just plug λ = 0.5 into the Poisson PMF, you get the familiar table that the comment itself lists:

- k = 0: 0.6065 → about 60.65% of bins are empty

- k = 1: 0.3033 → about 30.33% have exactly one entry

- k = 2: 0.0758 → about 7.58% have two

- k = 3: 0.0126 → about 1.26% have three

- k = 4: 0.00158 → about 0.158% have four

- k = 5: 0.000158 → about 0.0158% have five

- k ≥ 8: less than one in ten million

This is the statistical justification for CHM’s “bin-local” design. Even though updates may occasionally synchronize on a bin head (and bins start out as linked lists), in the common case—where hashes are sufficiently well spread—most bins stay very short, and contention is naturally limited to a tiny fraction of the table.

Treeification, in that framing, is not really about improving the average case of healthy workloads. It only becomes relevant once a bin grows past an unusually large threshold (default 8), and even then it’s treated more like a last resort than a default strategy. In practice, you can think of it as a defensive mechanism: it caps performance degradation in scenarios where collisions become abnormally severe—bad hashCode() implementations, skewed key distributions, or deliberate hash-flooding-style behavior—rather than something CHM expects to rely on routinely.

A Detour into Unsafe: How CHM Touches table[] Without “Normal” Java Array Access

If you look closely at the hottest parts of ConcurrentHashMap, you’ll notice something slightly unusual: it does not read and write table[i] using the ordinary tab[i] bytecode sequence.

Instead, it routes almost all element access through three helpers:

@SuppressWarnings("unchecked")

static final <K,V> Node<K,V> tabAt(Node<K,V>[] tab, int i) {

return (Node<K,V>)U.getReferenceAcquire(tab, ((long)i << ASHIFT) + ABASE);

}

static final <K,V> boolean casTabAt(Node<K,V>[] tab, int i,

Node<K,V> c, Node<K,V> v) {

return U.compareAndSetReference(tab, ((long)i << ASHIFT) + ABASE, c, v);

}

static final <K,V> void setTabAt(Node<K,V>[] tab, int i, Node<K,V> v) {

U.putReferenceRelease(tab, ((long)i << ASHIFT) + ABASE, v);

}

This looks like “just a different way to spell tab[i]”, but it’s actually a deliberate set of micro-optimizations with two goals:

- Control the exact Java Memory Model (JMM) semantics on the table slot read/write.

- Make the generated machine code cheaper and more predictable (especially on the read path).

Let’s unpack what’s going on.

Why not just use volatile Node<K,V>[] table and do tab[i]?

CHM’s table reference is volatile:

transient volatile Node<K, V>[] table;

…but note what is not volatile here:

- individual array elements are not volatile in Java

tab[i]is just a plain load of a reference from an array slot

So if CHM wants to do the classic lock-free “check slot / CAS install node” pattern safely, it needs element-level atomics and well-defined ordering on the slot itself.

That’s what these helpers provide:

tabAt()is an acquire load of the array element.setTabAt()is a release store to the array element.casTabAt()is the atomic “install if still null” primitive.

This is the core trick: the array is a normal Java array, but CHM treats each slot like an atomic variable.

Acquire vs. Volatile: Paying Only for What You Need

A normal “volatile read” in Java is stronger than an acquire load. Likewise, a “volatile write” is stronger than a release store.

CHM intentionally uses acquire/release when it can, instead of defaulting to full volatile semantics everywhere.

When you read a bin head, CHM mostly wants publication safety:

- If another thread already published a

Nodeintotab[i], - then after I observe that reference,

- I must also observe the

Node’s initialized fields (and whatever it links to), in a sane order.

That is exactly the use case for acquire:

If a thread performs a release store that publishes an object reference, then another thread that performs an acquire load and sees that reference is guaranteed to see the writes that happened-before the release.

So tabAt() uses getReferenceAcquire(...): it’s the “I’m about to dereference what I just found” load.

When CHM installs a brand new bin head (or replaces a bin during treeification / migration), it wants the opposite direction:

- initialize node fields

- then publish the node pointer into

tab[i] - and ensure readers that see the pointer also see the initialization

That’s a textbook release store, so setTabAt() uses putReferenceRelease(...).

This is a neat pattern because it’s surgical: it provides the “safe publication” guarantee without forcing every table-slot access to behave like a full volatile read/write.

CAS on an array slot without an AtomicReferenceArray

You might be thinking: “Why not use AtomicReferenceArray<Node<K,V>>?”

Because it would be much heavier:

- extra object wrapper

- extra indirection and range checks

- a less JIT-friendly shape for tight loops

- and historically,

Atomic*ArrayAPIs weren’t great for extracting “just acquire/release” semantics either

CHM instead computes the raw memory offset of tab[i]:

((long)i << ASHIFT) + ABASE

ABASE: base offset where the first element starts inside the array objectASHIFT: shift amount such that(i << ASHIFT)equalsi * elementScale

This makes the access look like “pointer + scaled index”, which is exactly what HotSpot wants to see if it’s going to generate tight machine code.

Unsafe as a Way to Eliminate Unnecessary Bounds Checks

Another, less obvious reason ConcurrentHashMap relies on Unsafe for table access is bounds-check elimination.

In ordinary Java code, an array access like tab[i] implicitly carries two checks:

- a null check on the array reference

- a range check ensuring

0 <= i < tab.length

HotSpot is often able to eliminate these checks via bounds-check elimination (BCE), but only when it can prove that the index is always in range. In simple loops, this proof is straightforward. In real-world concurrent data structures, it often isn’t.

ConcurrentHashMap’s hot paths are full of patterns that make BCE harder:

- retry loops with multiple exits

- index calculations involving masking, CAS retries, and resize cooperation

- control flow that depends on concurrent state (

MOVED, forwarding nodes, etc.)

Even when the index is logically guaranteed to be in range, the compiler may fail to prove it and conservatively emit a bounds check on every access.

By computing the element address explicitly—

((long)i << ASHIFT) + ABASE

—CHM avoids the bytecode-level array bounds checks by using raw-address access via Unsafe. At that point, the JVM treats the operation as a raw memory access: no range check is inserted, because the responsibility has shifted to the programmer.

This is not “free performance.” It is a deliberate trade-off.

Using Unsafe means the JVM no longer protects you from out-of-bounds access. If the index calculation is wrong, the failure mode is no longer a clean ArrayIndexOutOfBoundsException, but memory corruption or a VM crash. In other words, Unsafe does not optimize bounds checks—it opts out of them.

For code like ConcurrentHashMap, this trade-off is acceptable. The index invariants are carefully maintained, heavily tested, and relied upon by the entire implementation. Avoiding redundant bounds checks in the hottest paths helps keep the common-case fast path as short and predictable as possible.

Unsafe is therefore best understood not as a general-purpose performance hammer, but as a precision tool: useful when the compiler cannot prove safety, but the programmer can.

Element Count: Fast Updates, Expensive Reads (and a Resize Heuristic)

ConcurrentHashMap has an interesting problem to solve: it needs some notion of “how many elements are in the map,” but it can’t afford to turn every put() into a scalability bottleneck. The solution it uses is essentially a specialized, inlined version of LongAdder’s core idea: keep a striped set of counters so increments don’t all fight over the same cache line.

Concretely, CHM maintains a baseCount plus an optional CounterCell[] array. Updates try to hit the fast path first (CAS on the base), and when contention is detected, the map “fans out” into multiple CounterCell so different threads can increment different cells concurrently. The source comment explicitly calls this “a specialization of LongAdder,” and notes that it relies on contention-sensing to decide when to create more cells.

The key trade-off is that updates are cheap, but accurate reads are expensive. To compute the current size, CHM has to do baseCount + sum(counterCells[i]), which touches a bunch of distinct memory locations:

final long sumCount() {

CounterCell[] cs = counterCells;

long sum = baseCount;

if (cs != null) {

for (CounterCell c : cs)

if (c != null)

sum += c.value;

}

return sum;

}

Under heavy put() traffic, those cells are actively being modified by other cores, so a “full sum” can end up bouncing cache lines around and creating exactly the sort of cache thrashing you don’t want on a hot update path. CHM’s own comment calls out this risk directly: the counter mechanics avoid contention on updates, but can encounter cache thrashing if read too frequently.

That’s why CHM avoids the most obvious approach—checking count >= threshold on every insertion. Instead, it uses a simple heuristic to make the expensive counter read rare: under contention, resizing is only attempted when adding to a bin that already contains two or more nodes (i.e., when you’re inserting into a “collided bin,” not an empty/singleton bin).

The comment even quantifies the benefit

To avoid reading so often, resizing under contention is attempted only upon adding to a bin already holding two or more nodes. Under uniform hash distributions, the probability of this occurring at threshold is around 13%, meaning that only about 1 in 8 puts check threshold (and after resizing, many fewer do so).

/**

* Adds to count, and if table is too small and not already

* resizing, initiates transfer. If already resizing, helps

* perform transfer if work is available. Rechecks occupancy

* after a transfer to see if another resize is already needed

* because resizings are lagging additions.

*

* @param x the count to add

* @param check if <0, don't check resize, if <= 1 only check if uncontended

*/

private final void addCount(long x, int check) {

CounterCell[] cs; long b, s;

if ((cs = counterCells) != null ||

!U.compareAndSetLong(this, BASECOUNT, b = baseCount, s = b + x)) {

CounterCell c; long v; int m;

boolean uncontended = true;

if (cs == null || (m = cs.length - 1) < 0 ||

(c = cs[ThreadLocalRandom.getProbe() & m]) == null ||

!(uncontended =

U.compareAndSetLong(c, CELLVALUE, v = c.value, v + x))) {

fullAddCount(x, uncontended);

return;

}

if (check <= 1) // check = bin size(count)

return;

s = sumCount();

}

if (check >= 0) {

Node<K,V>[] tab, nt; int n, sc;

while (s >= (long)(sc = sizeCtl) && (tab = table) != null &&

(n = tab.length) < MAXIMUM_CAPACITY) {

int rs = resizeStamp(n) << RESIZE_STAMP_SHIFT;

if (sc < 0) {

if (sc == rs + MAX_RESIZERS || sc == rs + 1 ||

(nt = nextTable) == null || transferIndex <= 0)

break;

if (U.compareAndSetInt(this, SIZECTL, sc, sc + 1))

transfer(tab, nt);

}

else if (U.compareAndSetInt(this, SIZECTL, sc, rs + 2))

transfer(tab, null);

s = sumCount();

}

}

}

Cooperative Resize: Sharing the Rehash Work

ConcurrentHashMap also has a distinctive mechanism for resizing: cooperative resize. Instead of making a single thread perform the entire rehash/transfer in one long, monolithic step, CHM spreads the work across multiple threads. Threads doing ordinary operations—put, remove, and even some reads—can detect that a resize is in progress and then help move a small chunk of bins into the new table. In effect, the resize is completed in parallel, incrementally, by the threads that are already interacting with the map.

This design has a few practical benefits. It avoids a stop-the-world style “everything stalls while we resize” phase, and it prevents one unlucky thread from paying the entire resize cost alone. More importantly, even if a resize takes a while under sustained updates, CHM can install ForwardingNode to redirect operations toward the new table, which helps keep the map responsive and reduces the risk of tail-latency blowups.

I’ll stop here for now—CHM’s resize protocol is deep enough that it deserves its own dedicated section, and including all the details here would make this part unnecessarily long.

4) Lock-Free Open Addressing (Cliff Click’s NonBlockingHashMap)

So far we’ve covered three concurrency strategies:

- one global lock (

synchronizedMap) - sharding (

DashMap-style) - and Java’s

ConcurrentHashMap(CAS-first, bin-local locking, cooperative resize)

Cliff Click’s NonBlockingHashMap (NBHM) explores a fourth point in the design space: an open-addressed hash table where updates are coordinated via CAS-based slot claiming, and resizing is handled by cooperative copying rather than a stop-the-world phase.

The class header doesn’t hide its ambition: it explicitly positions itself as a lock-free alternative to ConcurrentHashMap, emphasizing non-blocking updates and scalability under high update rates. In fact, the comment is extremely confident about scalability, claiming linear scaling “up to 768 CPUs on a 768-CPU Azul box,” even under 100% updates or 100% reads.

I’m not treating these numbers as gospel—they depend heavily on workload, JVM, and hardware—but the claim is still a useful signal. NBHM was designed with high update throughput at large core counts as a first-class goal, not as an afterthought.

A Single Table Snapshot, Atomically Replaced

NBHM’s main table state lives in a single Object[] called _kvs.

private transient Object[] _kvs;

And yes—replacement really means replacement: _kvs can be swapped as a single atomic operation via Unsafe:

private final boolean CAS_kvs( final Object[] oldkvs, final Object[] newkvs ) {

return _unsafe.compareAndSwapObject(this, _kvs_offset, oldkvs, newkvs );

}

The layout inside _kvs is also very data-oriented:

kvs[0]holds a control structureCHMkvs[1]holdsint[] hashes(memoized full hashes)- then pairs of

{Key, Value}start from slot 2

private static final CHM chm (Object[] kvs) { return (CHM )kvs[0]; }

private static final int[] hashes(Object[] kvs) { return (int[])kvs[1]; }

private static final Object key(Object[] kvs,int idx) { return kvs[(idx<<1)+2]; }

private static final Object val(Object[] kvs,int idx) { return kvs[(idx<<1)+3]; }

private static final int len(Object[] kvs) { return (kvs.length-2)>>1; }

One subtle choice here is why CHM is stored inside _kvs instead of having _kvs inside CHM. The comment spells it out:

The

CHMinfo is used during resize events and updates, but not during standard ‘get’ operations. I assume ‘get’ is much more frequent than ‘put’. ‘get’ can skip the extra indirection of skipping through theCHMto reach the_kvsarray.

A Note on the Internal CHM: Control Plane

One slightly confusing aspect of NonBlockingHashMap is the presence of a nested class called CHM. At first glance, this looks odd: why does a lock-free hash map contain something named “CHM” at all? Is this just a leftover from ConcurrentHashMap?

It isn’t. In NBHM, CHM plays a very specific role: it acts as the control plane for the hash table, while the actual keys and values live entirely in the data plane (_kvs).

CHM is not a bucket table.

It does not store keys or values.

It is not involved in the normal get() probe loop beyond a single volatile read.

In particular, get() never walks through CHM to find entries. That work is done purely against the _kvs array. This separation is intentional.

CHM groups together all the global coordination state needed to make the lock-free protocol work:

Size and slot counters

These track how many live key/value pairs exist and how many key slots have ever been claimed (important with tombstones)

private final Counter _size;

private final Counter _slots;

Importantly, these are implemented as Counters backed by ConcurrentAutoTable, which shards updates across multiple internal cells (LongAdder/CounterCell-style) to minimize contention under concurrent increments.

Resize state

This single field answers the question: “Is a resize in progress, and if so, where is the new table?”

volatile Object[] _newkvs;

Copy coordination

These counters distribute resize work across threads and determine when it is safe to promote the new table.

volatile long _copyIdx;

volatile long _copyDone;

Resize heuristics

This logic decides when reprobe rates or tombstone density are bad enough to justify starting a resize.

private final boolean tableFull(int reprobe_cnt, int len)

In short, CHM is where NBHM centralizes shared state that must be seen consistently across threads, but that is orthogonal to the actual key/value lookup logic.

Hash Memoization: Avoiding Expensive equals() on the Hot Path

One small but telling detail in NonBlockingHashMap is the presence of a dedicated hashes[] array:

// Slot 1 holds full hashes as an array of ints.

private static final int[] hashes(Object[] kvs) { return (int[])kvs[1]; }

At first glance, this may look redundant—after all, the hash of the lookup key is already computed once at the beginning of get or put. But the motivation becomes clear once you look at where this array is actually used.

During probing, key comparison is performed via keyeq(...):

private static boolean keyeq(Object K, Object key, int[] hashes, int idx, int fullhash) {

return

K == key ||

((hashes[idx] == 0 || hashes[idx] == fullhash) &&

K != TOMBSTONE &&

key.equals(K));

}

The critical line is the hash check:

hashes[idx] == 0 || hashes[idx] == fullhash

This is a cheap negative filter. If the memoized hash stored in the slot does not match the lookup key’s hash, the code can immediately skip the expensive equals() call. Only when the hashes match (or when the hash is still zero) does it fall back to a full key comparison.

This matters because equals() is often the most expensive operation in the probe loop:

- it is a virtual call,

- it may be megamorphic under mixed key types,

- and it often involves additional memory reads inside the key object.

In contrast, reading hashes[idx] is just a single load from a dense int[], which is far more cache- and JIT-friendly.

If you want a concrete example of how much

Objects.equalscan hurt hash map performance on the hot path, I wrote up a detailed case study in my previous post.

A Familiar Idea if You’ve Seen SwissTable

Conceptually, this optimization is strikingly similar to SwissTable’s design.

SwissTable also tries very hard to avoid expensive key comparisons on the hot path. Instead of storing full hashes, it stores a small fingerprint (H2) in a compact metadata array. Lookups first compare these fingerprints in bulk; only candidate slots proceed to a full key comparison.

The underlying idea is the same in both designs:

Use a cheap, cache-friendly hash-derived check to rule out most mismatches before touching the actual key.

NBHM uses a full int hash per slot; SwissTable uses a compact 7-bit tag packed into control bytes. The data layout and SIMD tricks differ, but the motivation is identical: push expensive work (equals, pointer chasing) as far off the hot path as possible.

Seen in that light, hashes[] in NonBlockingHashMap is not just a micro-optimization—it’s an early example of the same principle that SwissTable later takes much further with explicit metadata arrays and vectorized probing.

Unsafe Everywhere: Element-level CAS on Keys and Values

NBHM doesn’t use AtomicReferenceArray. Instead it uses Unsafe to CAS individual array elements, exactly like we saw in ConcurrentHashMap’s tabAt/casTabAt.

private static final boolean CAS_key( Object[] kvs, int idx, Object old, Object key ) {

return _unsafe.compareAndSwapObject( kvs, rawIndex(kvs,(idx<<1)+2), old, key );

}

private static final boolean CAS_val( Object[] kvs, int idx, Object old, Object val ) {

return _unsafe.compareAndSwapObject( kvs, rawIndex(kvs,(idx<<1)+3), old, val );

}

This is the foundation for the whole algorithm:

- keys and values are stored in plain

Object[] - each slot update is guarded by a single CAS

Sentinel States: TOMBSTONE and Prime

Since this is open addressing, deletion can’t simply “clear” a slot without breaking probe chains. NBHM uses a tombstone marker:

private static final Object TOMBSTONE = new Object();

But it also needs a way to say “this slot is being migrated to a new table.” That’s what the Prime wrapper is for:

private static final class Prime {

final Object _V;

Prime( Object V ) { _V = V; }

static Object unbox( Object V ) { return V instanceof Prime ? ((Prime)V)._V : V; }

}

And there’s even a special “primed tombstone”:

private static final Prime TOMBPRIME = new Prime(TOMBSTONE);

This might look like a quirky implementation detail, but it’s actually the central mechanism that makes cooperative resizing work.

get(): Open Addressing + One Volatile Read for Safe Publication

The read path is a classic probe loop:

int idx = fullhash & (len-1);

while (true) {

final Object K = key(kvs,idx);

final Object V = val(kvs,idx);

if( K == null ) return null;

...

idx = (idx+1)&(len-1);

}

The interesting part is the comment right after reading K and V. NBHM does a volatile read of chm._newkvs before comparing keys:

final Object[] newkvs = chm._newkvs;// VOLATILE READ before key compare

And the comment explains why:

- without a volatile read, a thread could observe the key reference in the table but still see an uninitialized key body (publication / reordering)

- similarly, it wants a happens-before edge before returning a newly inserted value

The important point is not “volatile is slow,” but where NBHM chooses to pay for it:

It pays one volatile read per probe step, because it wants a clean happens-before boundary on the hot path.

If the key matches and the value is not Prime, get can return immediately:

if( keyeq(K,key,hashes,idx,fullhash) ) {

if( !(V instanceof Prime) )

return (V == TOMBSTONE) ? null : V;

// Key hit - but slot is (possibly partially) copied to the new table.

// Finish the copy & retry in the new table.

return get_impl(topmap, chm.copy_slot_and_check(...), key, fullhash);

}

If it sees a Prime, it does not try to interpret it locally. It treats it as a “migration in progress” marker:

- help copy the slot

- retry in the new table

putIfMatch(): The Whole Map in One Function

Almost all mutations funnel through putIfMatch:

putusesNO_MATCH_OLDputIfAbsentusesTOMBSTONEremoveusesTOMBSTONEas the new valuereplaceusesMATCH_ANYor an expected old value

public TypeV put(TypeK key, TypeV val) {

return putIfMatch(key, val, NO_MATCH_OLD);

}

public TypeV putIfAbsent(TypeK key, TypeV val) {

return putIfMatch(key, val, TOMBSTONE);

}

public TypeV remove(Object key) {

return putIfMatch(key, TOMBSTONE, NO_MATCH_OLD);

}

public TypeV replace(TypeK key, TypeV val) {

return putIfMatch(key, val, MATCH_ANY);

}

That design choice matters: correctness lives in one place.

Phase 1: Key-Claim (Atomic Slot Claiming)

The first half of putIfMatch is labeled “Key-Claim stanza.” It spins until it can claim a key slot or decides the table must resize.

while( true ) { // Spin till we get a Key slot

V = val(kvs,idx);

K = key(kvs,idx);

if( K == null ) { // Slot is free?

if( putval == TOMBSTONE ) return putval; // never-been here

if( CAS_key(kvs,idx, null, key ) ) {

chm._slots.add(1);

hashes[idx] = fullhash;

break;

}

// CAS to claim the key-slot failed.

K = key(kvs,idx);

assert K != null;

}

...

}

This is the key lock-free move:

- empty slot (

K == null) is claimed withCAS_key(null → key) - key slots “become used” via

_slots - the full hash is memoized

And then there’s an extremely important comment about Java CAS:

Java CAS returns only a boolean, so on failure you don’t get the “witness” value that caused it to fail. Re-reading cannot reliably recover the witness because another thread might change the slot again. So NBHM avoids “apparent spurious failure” by not allowing keys to ever change.

That explains a non-obvious invariant:

Key slots are forever claimed. Deletes don’t remove keys; they tombstone values.

That single invariant makes a lot of lock-free reasoning tractable.

Phase 2: Resize Detection on the Write Path

Before actually CASing the value, NBHM decides whether it must start/participate in a resize.

It forces resize when:

- it’s inserting a new value into a previously-null value slot and

tableFull(...)says reprobes are too high, or - it observed a

Prime(meaning a migration protocol is in play)

if( newkvs == null &&

((V == null && chm.tableFull(reprobe_cnt,len)) ||

V instanceof Prime) )

newkvs = chm.resize(topmap,kvs);

if( newkvs != null )

return putIfMatch(topmap, chm.copy_slot_and_check(...), key, putval, expVal);

So writes do not “fight” a resize. They join it.

Phase 3: Value CAS + Size Accounting

Once it’s sure it’s operating on a stable table (no newkvs), it applies the expected-value logic and CASes the value slot:

if( CAS_val(kvs, idx, V, putval ) ) {

if( expVal != null ) {

if( (V == null || V == TOMBSTONE) && putval != TOMBSTONE ) chm._size.add( 1);

if( !(V == null || V == TOMBSTONE) && putval == TOMBSTONE ) chm._size.add(-1);

}

return (V==null && expVal!=null) ? TOMBSTONE : V;

}

Two details worth noticing:

- values monotonically go from null → non-null, and deletion is represented by

TOMBSTONE - size is maintained via counters (

_size,_slots) that avoid global locking

Resizing: Cooperative Copying with _newkvs, _copyIdx, _copyDone

The resize protocol lives in CHM.

Starting a resize is the familiar “publish a new table once” pattern:

volatile Object[] _newkvs;

Object[] newkvs = _newkvs; // VOLATILE READ

if( newkvs != null ) {

return newkvs;

}

// allocate and then CAS it in

if( CAS_newkvs(newkvs) ) {

topmap.rehash();

}

After _newkvs becomes non-null, all threads can see that a new table exists, and the rest becomes cooperative copying.

Work distribution uses two counters:

_copyIdx: claims chunks of copy work_copyDone: tracks how many slots are confirmed-copied (used for promotion)

volatile long _copyIdx = 0;

volatile long _copyDone= 0;

Each helper thread claims a chunk (MIN_COPY_WORK) and repeatedly calls copy_slot(...).

for( int i=0; i<MIN_COPY_WORK; i++ )

if( copy_slot(topmap,(copyidx+i)&(oldlen-1),oldkvs,newkvs) )

workdone++;

if( workdone > 0 )

copy_check_and_promote(topmap, oldkvs, workdone);

Promotion is exactly what you’d expect: once copying is complete, swap _kvs at the top-level:

if( copyDone+workdone == oldlen &&

topmap._kvs == oldkvs &&

topmap.CAS_kvs(oldkvs,_newkvs) ) {

topmap._last_resize_milli = System.currentTimeMillis();

}

This resembles ConcurrentHashMap’s cooperative resize in spirit, but the mechanism is different:

- CHM redirects bins via forwarding nodes

- NBHM redirects via per-slot

Primemarkers and table pointers (_newkvs)

copy_slot: The Heart of the Protocol

copy_slot is where the “Prime trick” pays off.

The algorithm is:

- prevent fresh updates in the old table by forcing empty keys to

TOMBSTONE(minor optimization) - box the old value into

Prime(oldVal)so nobody can update it in-place - copy the unboxed value into the new table, but only if it was

nullthere - slam the old value down to

TOMBPRIMEso others stop trying to copy it

Object oldval = val(oldkvs,idx);

while( !(oldval instanceof Prime) ) {

final Prime box = (oldval == null || oldval == TOMBSTONE) ? TOMBPRIME : new Prime(oldval);

if( CAS_val(oldkvs,idx,oldval,box) ) {

if( box == TOMBPRIME ) return true;

oldval = box;

break;

}

oldval = val(oldkvs,idx);

}

...

boolean copied_into_new =

(putIfMatch(topmap, newkvs, key, old_unboxed, null) == null);

...

while( !CAS_val(oldkvs,idx,oldval,TOMBPRIME) )

oldval = val(oldkvs,idx);

Two core invariants fall out of this:

- Once a value is boxed (

Prime), the old slot becomes effectively read-only. - Promotion is safe because NBHM can count null → non-null transitions in the new table (i.e., confirmed copies).

The Trade-off: Non-blocking != No Contention

NBHM avoids explicit locks, but it does not eliminate contention—it mostly moves it. Instead of “threads queue behind a lock,” contention shows up as cache-line ownership traffic from CAS, coherence, and the occasional global coordination step.

That said, the implementation is clearly trying to keep that contention from concentrating in one place. The high-frequency counters (_slots, _size) are not single hot variables; they are Counters backed by ConcurrentAutoTable, which shards updates in a LongAdder/CounterCell-like way. And the resize coordination counters (_copyIdx, _copyDone) are not bumped on every copied entry—they advance in coarse chunks (e.g., per ~1024 slots of copy work), keeping the shared-state traffic relatively infrequent.

This matters because it directly intersects with SwissTable-style metadata. If you bolt on high-frequency metadata writes (e.g., control bytes updated on every operation), you can still recreate the failure mode people warned about: false sharing at cache-line granularity—now layered on top of a code path that already pays for CAS and coherence under contention.

5) Closing Thoughts

Global locking, sharding, ConcurrentHashMap, and Cliff Click’s NonBlockingHashMap (NBHM) outline four very different ways to approach concurrency in a hash map. Each draws its contention boundary in a different place, and each pays for that choice with a different mix of simplicity, scalability, and implementation complexity.

The important takeaway is not that one approach is universally better, but that the shape of the data structure largely determines which concurrency strategies are viable. Techniques that work well for bucketed, pointer-based maps do not always translate cleanly to open-addressing designs, and vice versa.

In the next part, I’ll switch gears and look at how these ideas informed the design of SwissMap. Rather than re-implementing any one of these strategies wholesale, SwissMap selectively borrows from them—combining sharding, optimistic fast paths, and carefully chosen locking boundaries (while staying mindful of NBHM-style coherence costs) to fit the constraints of a SwissTable-style layout.

P.S. If you want the code

This post is basically the narrative version of an experiment I’m building in public: HashSmith, a small collection of fast, memory-efficient hash tables for the JVM.

ConcurrentSwissMap is still a work in progress. I’m planning to iterate on the design a bit more, run a proper set of benchmarks, and share the results in a follow-up post once things stabilize.