Limitations of Traditional Scalar State Machine Parsers

The JSON parsing algorithms we commonly use are based on scalar state machine parsers. Scalar parsers read the input string byte by byte, parsing it through state transitions within the state machine.

For example:

- When encountering a quotation mark (

"), it indicates the start of a string. - When encountering a colon (

:), it indicates that a value is expected next.

Below is a simplified pseudo-code representation of how a scalar parser works

parse(buf):

i = 0; stack = []

inStr = false; esc = false

root = null; key = null

while i < n:

c = buf[i]

if inStr:

if esc: str.append(c); esc = false

else if c == '\\': esc = true

else if c == '"': inStr = false; emit_string()

else: str.append(c)

i++; continue

if is_ws(c): i++; continue

if c == '"': inStr = true; str = ""; i++; continue

if c == '{': obj = {}; attach(obj); stack.push(obj); i++; continue

if c == '[': arr = []; attach(arr); stack.push(arr); i++; continue

if c == '}': stack.pop(); i++; continue

if c == ']': stack.pop(); i++; continue

if c == ':': expect_value = true; i++; continue

if c == ',': key = null; i++; continue

if starts_lit(buf,i,"true/false/null"): attach(literal); i+=len; continue

if is_num_start(c): num,cons = parse_number(buf,i); attach(num); i+=cons; continue

error()

return root

Traditional scalar parsers have the following drawbacks:

1. Many Branches

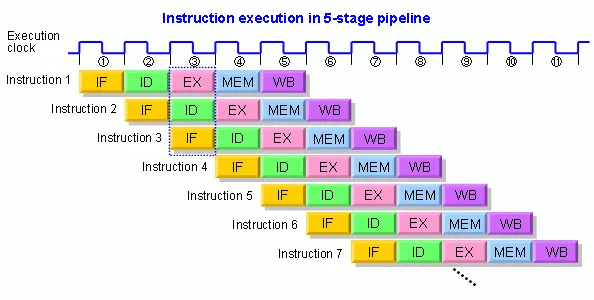

CPUs use pipelining to perform multiple stages of an instruction simultaneously to increase concurrency.

However, when the next instruction is unknown (such as in branch situations), the CPU cannot fetch the instruction and must wait.

To handle this, CPUs perform branch prediction to guess whether a branch will be true or false, and process instructions based on this prediction. If the prediction is correct, instructions are processed quickly. However, if the prediction is wrong, all previous operations are discarded, and the CPU has to restart from the beginning (IF stage), leading to performance loss.

Looking at traditional scalar parsers, they contain many branches (e.g., if and switch statements), and branch prediction failures occur frequently. As a result, the CPU cycles are wasted, causing performance degradation.

2. Increased Branching for String Internal/External Determination

When encountering a quotation mark ("), the parser starts and ends the string, but if there is an escape sequence (\\), it should not be considered as the end of the string. Additionally, the length of consecutive backslashes (e.g., \\\\) changes the validity of \".

These escape rules require many branches to be handled.

3. Sporadic Memory Access Patterns

Scalar parsers read strings byte by byte. For each byte, actions such as state checking or table lookups are performed. This leads to sporadic memory access patterns, which are highly inefficient in terms of locality. As a result, CPU cache (L1, L2) misses occur frequently.

SIMD JSON: What is it?

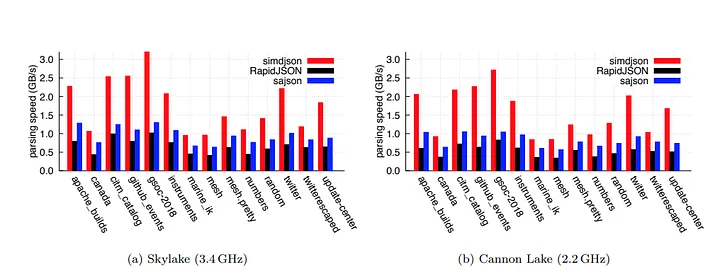

SIMD JSON is an algorithm that accelerates JSON parsing by actively utilizing SIMD(Single Instruction, Multiple Data) instructions in modern CPUs. The algorithm was first introduced in the 2019 paper “Parsing Gigabytes of JSON per Second” by Intel engineer Geoff Langdale and Daniel Lemire, a professor at the Universit´e du Qu´ebec.

According to the paper, SIMD JSON is about 2 to 5 times faster than traditional scalar parsers for JSON deserialization.

What is SIMD?

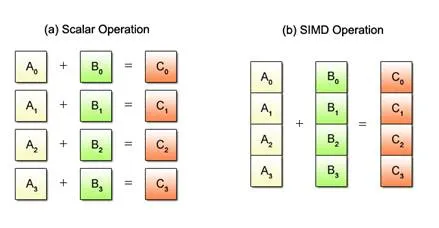

SIMD stands for Single Instruction, Multiple Data and refers to a hardware unit and instruction set that performs the same operation simultaneously on multiple pieces of data using a single CPU instruction.

Compared to traditional SISD (Single Instruction, Single Data) approaches, SIMD is much more efficient for parallel processing. Using SIMD operations reduces the number of instructions and branches needed for the same calculations and allows better utilization of CPU caches and memory bandwidth.

SIMD operations are highly efficient in domains requiring repetitive scalar operations, such as:

- Image/Audio/Video processing

- Encryption/Hashing, String Scanning, Pattern Matching

- ML vector/matrix operations

Modern CPUs are equipped with vector registers and vector execution units for SIMD support:

- x86: SSE/AVX/AVX2/AVX-512 units (vector registers XMM/YMM/ZMM, dedicated execution ports)

- ARM: NEON/SVE units (Q/N/Z registers)

Why is SIMD JSON Fast?

Vectorized Operations

Unlike scalar parsers, which process one byte at a time, SIMD JSON processes data in vector-sized chunks (e.g., 256 bits).

Branchless Operation

Most of the JSON parsing process in SIMD JSON is carried out through bitwise operations on vectors, eliminating most branch conditions. This reduces the performance loss due to branch prediction failures in the CPU pipeline.

SIMD JSON Algorithm Breakdown

The SIMD JSON algorithm consists of two main stages:

- Stage 1: JSON Structure Indexing

- Stage 2: JSON Parsing

Stage 1: Fast Structure Indexing (Pseudo-code)

for each vector block:

B = (block == '\\')

OD = calc_OD(B) // odd-length backslash ends

Q = (block == '"')

Q = Q & ~OD // remove escaped quotes

R = clmul(Q, all_ones) // in-string mask

S = classify([{]}:,) & ~R // structural char mask

W = classify(whitespace) // whitespace mask

P = ((S | W) << 1) & ~W & ~R // pseudo-structural starts

S = (S | P) & ~(Q & ~R)

extract_indices_from_bitset(S, out_indices)

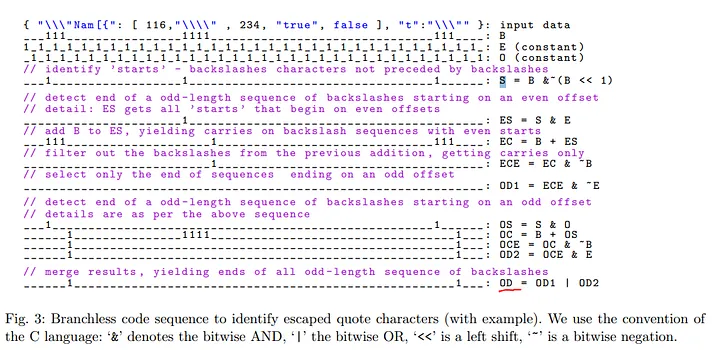

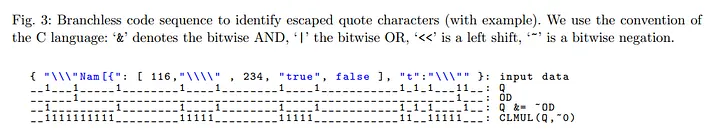

First, we divide the data block according to the size of the vector registers. Then, we calculate a mask (B) that marks the positions of backslashes in the data block. Next, we perform the following operations to calculate a mask (OD, odd-length ends) that marks positions where consecutive backslashes end with an odd length.

We then calculate a mask (Q) that marks the positions of quotation marks (") in the data block. We compute the valid (unescaped) quotation mark positions as Q &= ~OD. Afterward, we calculate a mask (R) that represents the string range (marked by 1s).

By performing a cumulative XOR (bitwise XOR for consecutive bits) operation on the valid quotation mark mask (Q & ~OD), we can derive the string range mask (R).

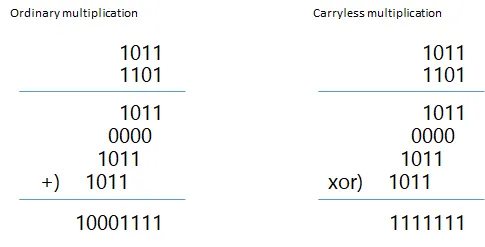

Using the CUMUL (carry-less multiplication) operation makes the cumulative XOR operation even more efficient. CUMUL, unlike regular multiplication, uses XOR after shifting instead of addition.

By applying the CUMUL operation to the mask indicating valid quotation mark positions and the mask where all bits are 1 (Q &= ~OD), we can quickly perform a prefix XOR operation (tracking quotation mark openings/closings) to compute the string range mask (R).

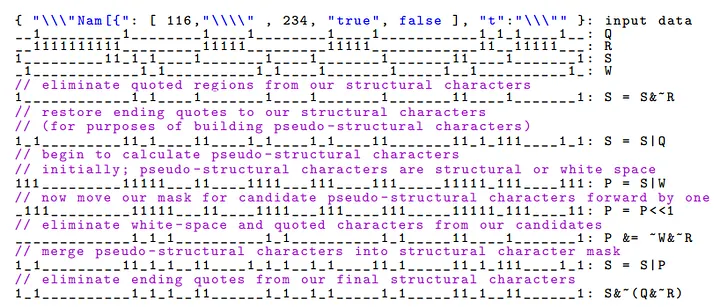

Next, we compute masks to identify the positions of structural and pseudo-structural characters:

Q: Quotation mark (") mask → Positions of quotation marks are marked as 1.R: String range mask → Positions within the string are marked as 1.S: Structural character mask (positions of{,},[,],:,,) → These positions are marked as 1.W: Whitespace mask (space,\n,\r,\t) → These positions are marked as 1.

Structural or whitespace characters inside the string are invalid, so we exclude them:

S = S & ~R: Exclude structural characters inside the string.W = W & ~R: Exclude whitespace inside the string.

We then include the quotation mark mask (Q) in the structural string mask:

S = S | Q

Using the rule that a value token (value) must follow a structural character (S) or whitespace (W), we create a mask (P) for the starting position of the value token.

P = (S | W) << 1: This mask identifies the positions following structural characters or whitespace.P &= ~W & ~R: Excludes whitespace and positions inside the string.

The resulting mask P accurately points to the start of the value token.

Next, we combine the structural string mask and the value token start positions to create a bitmask that marks the boundaries of all tokens:

S = S | P: this marks all token boundary points

Finally, we remove the quotation marks that mark the string boundaries from the mask S:

S & ~ (Q & ~ R)

Through this process, we obtain a bitmask where all the token boundary points are marked with 1s (e.g., 0001000100100000).

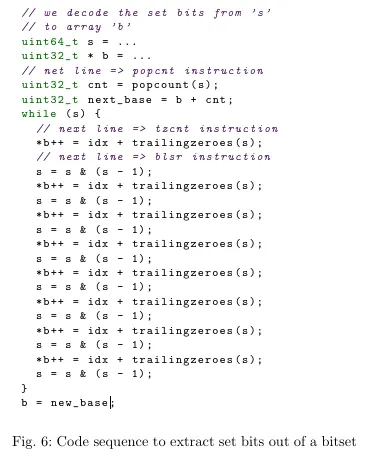

The next step is to convert this bitmask into an index format suitable for the parser (e.g., [3, 7, 10]). To do this, we use the tzcnt (trailing zero count) algorithm. The algorithm finds the index of the lowest bit set to 1 in the bitmask. For example, in the bitmask 00101000, the lowest bit set to 1 is at index 3. We add this index to the array and remove the least significant bit. This process is repeated.

Additionally, we apply loop unrolling to further optimize the process.

Stage 2: JSON Parsing

Once Stage 1 provides the token boundary indices, the actual parsing occurs. For each token, the appropriate parsing function is called to process the string, number, or other JSON data types.

Pseudocode for Stage 2: JSON Parsing

for i in out_indices:

switch chr[i]:

case '"':

parse_string_to_utf8();

write_tape_str();

case '-', '0'..'9':

parse_number();

write_tape_num();

case 't','f','n': // true, false, null

parse_atom();

write_tape_atom();

case '{','[':

push_scope();

write_open_with_link_slot();

case '}',']':

close_scope_and_backpatch_link();

References

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1902.08318

- https://simdjson.org/api/0.6.0/md_doc_ondemand.html

- https://m.blog.naver.com/ektjf731/223053617175?recommendTrackingCode=2

- https://m.blog.naver.com/ektjf731/223056327958?recommendTrackingCode=2

- https://www.officedaytime.com/simd512e/simdimg/pclmulqdq.html

- https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fftp.cvut.cz%2Fkernel%2Fpeople%2Fgeoff%2Fcell%2Fps3-linux-docs%2FCellProgrammingTutorial%2FBasicsOfSIMDProgramming.html&psig=AOvVaw3AuytgbRLjE84lJGyH9AoY&ust=1758635610339000&source=images&cd=vfe&opi=89978449&ved=0CBgQjhxqFwoTCOjsvqfC7I8DFQAAAAAdAAAAABAE